Here’s a little film I did for The Sky at Night (BBC4) all about How to Make a Comet. I actually made a comet in a lab, so much fun!

Category: My blog

5 Q’s about Rosetta

The Open University asked me to interview some of our Rosetta scientists about the mission and here’s the video.

On November 12th the Rosetta Philae lander is due to land on the surface of a comet. As a space scientist working with those who have instruments on board, I can’t wait. So, I met up with some of the Rosetta scientists at The Open University to ask them the top 5 questions I’m always being asked about the Rosetta mission.

Why bother to go to a comet?

I chatted to Ian Wright to find out more.

“We want to go because it’s there. It’s an object in our astronomical backyard and we want to know what it looks like and what it’s made of. We also want to know whether the water in a comet has a relationship with the water on Earth. If it does then we want to study the organics in the comet to know something about the organics that were brought to the surface of the early Earth.”

Why does the lander have harpoons?

One of the things about this landing is that it will be nothing like any landing to date on a planet or a moon. I chatted to Andrew Morse to find out more about why Rosetta needs harpoons.

“There are two harpoons on board and this is the first time they’ve been used in space. The gravity on a comet is so low that they’re needed to attach the lander to the comet but they’re not just required for the landing. The harpoons are also needed throughout the mission because as the comet becomes active, gases coming off the comet will act to push the lander away so they keep it firmly attached throughout the whole of the mission.”

Why is there an oven on board?

Simon Sheridan chatted to me about why Philae needs ovens.

“There are a number of ovens onboard the instrument, located behind the drill on a carousel. We need ovens because the Open University’s instrument, Ptolemy, is a mass spectrometer and we need to analyse the gases in the comet so we take the solid cometary material, pop it in the oven and heat it up to get the gases off that to analyse. The Ptolemy instrument is located inside the lander and the gases from the oven reach it via a pipe.”

But what if it crashes on landing?

The landing of the Rosetta Philae spacecraft is risky and there is the potential for a crash. But what would happen in these circumstances. I chatted to Geraint Morgan to find out more.

“The instruments including Ptolemy are already pre-programmed so will sniff the comet whatever happens, whichever way we land. Ptolemy is a miniature version of a lab instrument we have at the Open University and has similar functionality. We’ve been applying the knowledge we’ve developed with Ptolemy to several challenges back here on Earth including healthcare, safety equipment and also even measuring the quality of our drinking water.”

Could this mission save the world?

This could really seem like an over-claim. But is it? We only have to think back to the demise of the dinosaurs that were most likely wiped out by a comet colliding with the Earth. I went to meet Monica Grady to get her opinion.

“This mission couldn’t directly save the Earth but it could indirectly. Comets travel through the inner Solar System all the time. Some of them travel very near to the Earth and have even hit the Earth in the past. The more we know about comets; their composition, how tough they are, how easily they break up, the better it is so we can understand more about deflecting them away from the Earth. It might sound like science fiction but if the choice is between science fiction and global devastation because a comet hits then what choice do we have?”

All that’s left to say is good luck to all the Rosetta scientists on November 12th.

Why Rosetta is the greatest space mission of our lifetime – my article republished from The Conversation

Why Rosetta is the greatest space mission of our lifetime

By Natalie Starkey, The Open University

With only a week to go before the Rosetta spacecraft drops its Philae lander onto the surface of comet 67P, I wonder whether there will be another space mission in my lifetime that is so inspiring. Part of what has been so impressive is the length of time this mission has taken to finally get to the comet – 20 years since planning began (when I was still in high school), ten years since launch (when I was studying for my first degree). I feel very lucky that I am now employed as a space scientist at a time when all this work is coming to fruition.

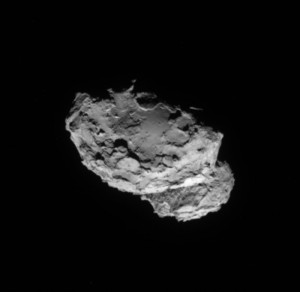

Rosetta has now reached the bizarrely shaped rubber-duck comet and it has spent three months mapping its surface in the hope of finding a suitable spot to place its Philae lander. This is a huge feat in itself. It is the first time a spacecraft has entered into orbit around a comet, which is a celestial body with almost no gravity.

The images Rosetta has sent back have allowed us to learn so much about this never-before-seen world. The European Space Agency (ESA) can already be proud of its achievements so far.

The Philae lander – packed with a science laboratory, harpoons and even ovens – gives the ESA a chance to do more. The hope is that Philae will help answer some of the most basic questions about our existence.

The original ambition for Rosetta was for it to be a sample-return mission: land on a comet and bring back samples to analyse on Earth. But the crippling costs of achieving this meant that it had to be scaled back: how about we just land on a speeding comet instead?

This strategy may cost less overall, but it wasn’t going to be much easier. On November 12, when Philae attempts to land, all manner of things can go wrong. The gravity of 67P is so small that Philae could hit the surface, bounce off and be lost in the emptiness of space.

We will nervously wait for news about Philae’s fate. After Philae leaves Rosetta, it will take about seven hours to reach the comet surface. If Rosetta achieves the comet landing, I believe it will be the most exciting space mission of my lifetime. (Of course, I wasn’t alive for the Apollo landings which will remain the most amazing space missions in history).

One could argue that there are many other missions in recent years that are just as impressive, if not more so, than Rosetta. It is usually the ones with the big backing from the US space agency NASA, such as the Curiosity rover mission that spring to mind. However, most recently I was impressed with the Indian mission, Mangalyaan, that entered into Mars orbit this year after a ten-month journey – and with a tiny budget.

However, I have to admit, it sneaked up on me – I wasn’t really aware of Mangalyaan until a couple of days before the orbit was announced. This is where we find that a bit of quality promotion goes a long way.

Just take NASA’s Curiosity as an example, which continuously shares images of Mars’ surface. Even before it reached there, videos such as such as the famous seven minutes of terror captivated audiences. The mission itself is of course impressive. Mars is about 150 times farther from the Earth than the moon. And the crazy sky-crane landing, getting it down successfully I was sure it would end in failure. But it didn’t. The science continues to beamed back by the rover.

ESA has started to play catch-up with NASA and its most recent video release, called “Ambition”, really took me by surprise. It is definitely something out of the ordinary: a big-budget-style sci-fi movie, with famous actors, such as Aidan Gillen of Game of Thrones fame, and a subtle yet powerful message relating to the Rosetta mission.

Whatever the movie cost to make, it was definitely worth it. We desperately need to inspire the space scientists of the future – and I spend a lot of time in schools chatting to children about their life ambitions in the hope they might want to follow me on a science career path.

My main words of advice to these children are similar to those that most stuck with me: aim high. I wanted to be an astronaut, so maybe I haven’t made it there (yet), but being a space scientist in such amazing times, when we are attempting to land on the surface of a comet, is not a bad second best.

![]()

Natalie Starkey receives funding from the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC). She is affiliated with The Open University.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Read the original article.

Filming filming…all in the name of Rosetta

It’s been a busy week for me as I’ve ventured into the world of TV presenting! And what fun it’s been. I had a little warm up act last week when I presented a video for The Open University answering 5 Questions all about Rosetta. This included things like ‘Why do we need harpoons on board?’ and ‘Why does the lander have an oven?’. If you want to find out the answers then you’ll have to watch the video which I’ll post a link to very soon! Here’s a snap of me chatting to Dr Simon Sheridan about the ovens though…we’re both holding one in our hands, they’re tiny!

Yesterday I was busy all day filming a segment for the next episode of Sky at Night. This is going to be an hour long special all about the landing, due to air on November 16th, and I did a piece on ‘How to make a comet’ where I got, for the first time, to do the ‘dry ice’ comet experiment. It was lots of fun and we did manage to actually make 2 comets that looked somewhat like the real thing. Having used photocopy toner for our ‘organic’ material, they turned out to be just as dark as 67P!

Yesterday I was busy all day filming a segment for the next episode of Sky at Night. This is going to be an hour long special all about the landing, due to air on November 16th, and I did a piece on ‘How to make a comet’ where I got, for the first time, to do the ‘dry ice’ comet experiment. It was lots of fun and we did manage to actually make 2 comets that looked somewhat like the real thing. Having used photocopy toner for our ‘organic’ material, they turned out to be just as dark as 67P!

Before the historic comet landing, Philae faces many dangers – republished article from The Conversation

Since I haven’t had time to write any updates about the Rosetta mission (I’ve been busy in the lab, honest!), I thought I would re-publish this one from ‘The Conversation’ website by my Head of Department Professor Monica Grady. A little update on the dangers faced by the Philae lander.

Before the historic comet landing, Philae faces many dangers

By Monica Grady, The Open University

“Are we nearly there yet?” is a plaintive query that most parents learn to dread, especially if uttered while halted in a traffic jam in the baking hot sun. At least the Rosetta spacecraft has not had to deal with interplanetary traffic on its way to its destination of Comet 67P Churyumov-Gerasimenko. It is also well-protected against solar radiation. But the scientists working on the Philae lander might be forgiven for feeling as if their journey is never going to end, as Rosetta makes increasingly delicate manoeuvres towards its final orbit.

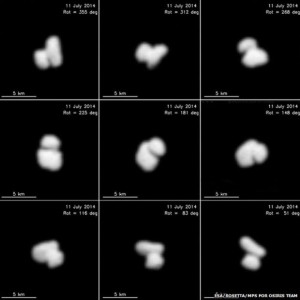

Over the past few weeks we have been captivated by detailed images of the comet: progressing from an out-of-focus blob that became a poorly focused duck, to the beautiful pictures of craters and rubble-strewn regions distributed across what must be one of the oddest-shaped bodies ever to have been photographed by a spacecraft.

Riding the duck

Images of the two unequally sized lobes, joined in the centre by a narrower bridge of material, have already led to a whole series of questions that have to be answered before the mission can progress successfully. Is Comet 67P two bodies that have come together during an impact? Or is it a single body that has been eroded by impacts? Are the two lobes of the same density?

Instruments on board Rosetta are mapping the composition of the surface and scientists now have a good idea of how the composition varies across the cometary nucleus. On September 26, Rosetta starts a series of measurements on the “night side” of 67P. This doesn’t mean that Rosetta is operating in the dark, but that its instruments are pointing towards the part of the comet’s surface which isn’t illuminated. This is so that we can learn more about the thermal properties of the surface, which has already been found to be hotter than expected by some 50 degrees.

A safe landing for Philae depends upon very accurate knowledge of the physical and thermal properties of 67P. To carry out such measurements, Rosetta will need drop into an orbit around 20km above the comet’s surface. Eventually however, Rosetta should be orbiting only about 1km above the surface, a position at which the Philae lander will be released from the mother-ship to make its descent to its destination.

ESA/Rosetta/NAVCAM, CC BY

While the detailed images of the comet’s surface have been fascinating, they have also revealed that Philae faces more dangers that we had considered. Much thought has been given to exactly where on the comet Philae will land. The best site will be a trade-off between its flatness, its slope, the amount of boulders scattered across the surface and how the site is illuminated.

Danger ahead

These parameters are all important. If the landing site is too bumpy or has too great a slope, it is likely that the lander will fall over rather than stay upright. If that happens, there is no way for it prop itself back up. Similarly, if there are too many boulders on the surface and one of the three legs hits a boulder, then again the lander will be unstable.

Illumination is also important: too much and the instruments will fry, too little and the battery will drain and not recharge.

Considering all those factors, two weeks ago, ESA announced the preferred landing site to be “site J”, on the top of the smaller of the two lobes which make up the comet. So now we know the proposed place on the comet where Philae will land, preparations are moving towards finalising the actual landing date.

November 11 is widely spoken of as when the landing will take place, and this should be confirmed by ESA very soon. The schedule of events on that day, however, will be unclear until mid-October. This is because Rosetta will continue mapping the surface of the comet, observing any changes, for example the emission of volatiles. If site J suddenly becomes active, such that it is no longer safe to land there, then the back-up landing site – “site C” – will be studied. Site C is on the other lobe of the comet, so a new set of launch trajectories and site characterisation would be required, possibly delaying the landing by up to a month.

Whenever the landing does happen, though, it is going to be nail-biting for the mission operators. The low gravity of 67P means that there is a real possibility that Philae could bounce straight back into space once it hits the surface. To prevent this, as it approaches, Philae will fire a harpoon into the comet, anchoring the spacecraft to its target. As Philae settles, its legs will take hold, and scientists on Earth will be hoping that all systems are now “go” for the next stage of the mission.

![]()

Monica Grady does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Read the original article.

The Sky at Night – How to Catch a Comet

The new Sky at Night episode was aired last night at 11pm on BBC4 which was a bit late for me so I just watched it on iPlayer where it’s available for 6 more days so catch it quick. (The clip of my interview is also available here). I was interviewed by Maggie Aderin-Pocock about my beautiful comet dust and you can see a picture of us above after the interview which was such fun. I think they did a great job with the programme too as it’s really informative with Chris Lintott having gone over to ESOC to speak to some of the mission scientists and engineers. Maggie was based at The Open University showing off our pretty summery campus, the lander model and you might also spot ‘Comet Starkey’ (as it’s being called), and this was the comet sculpture I had made for The Royal Society exhibit (unfortunately not a real comet with my name!). So, I hope you enjoy the show.

My next paper: weird comet dust!

My next paper published in Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta is now available online as an article ‘In Press’ here but the full edited version will be published soon. I have managed to get this paper published as Open Access which is fantastic because it means that everybody can get hold of it even if they don’t belong to a university that subscribes to the journal, or if they don’t belong to a university at all.

I have always referred to this paper as the ‘weird IDP paper’ because it discusses 2 IDPs (pieces of comet dust) that are a bit different and strange compared to all the others I’ve measured previously. One of them, called Balmoral*, contains some very heavy oxygen isotope ratios indicating that it has sampled an early Solar System reservoir only observed once before, and that was in a meteorite sample called Acfer 094. The other sample, called Lumley, is quite a large IDP and is really variable in composition across just small regions of the sample. I’ve not really seen this kind of diversity before and it indicates (or so I think) that the comet from which this particle originated was itself made up of a range of earlier comets (or primitive cometary bodies) of varied composition that were maybe formed in different locations in the early Solar System, that were disrupted and re-formed again. It just goes to show that IDPs, and comets in general have so much to show us. The problem is that the comet dust is just so small and hard to come by. Here’s hoping the Rosetta mission can shed more light on the mysteries of the early Solar System but in the meantime I’ll keep analysing my pieces of dust.

*I name my IDPs after castles (that I’ve visited) in the UK. Balmoral is the Queen’s castle in Scotland and Lumley is a castle in County Durham.

Rosetta orbit insertion happens tomorrow!

For many people August is holiday time, but not for me. I’m back in work after a break in July and raring to go again. And there’s so much going on. Obviously first things first, Rosetta meets the beautiful comet 67P/C-G and what a surprise that’s been for all of us to find out that it’s a binary comet. The initial shape models were completely wrong, but we were warned they might be totally inaccurate at the time. The first good images we got of 67P were so exciting, even if the comet was named the rubber duck after that (see above). Now we are just some 200km from the comet we’re starting to see the detailed texture of the surface (see image below). This is really exciting because we’ve not seen a comet in this much detail before…and it’s only going to get better as Rosetta continues to map the surface of 67P and will surely reveal even more exciting features. Fingers crossed the mission continues to go well and we can make it through to the landing phase in November.

In relation to comets and Rosetta, The Sky at Night on BBC4 this Sunday have a special programme called ‘How to Catch a Comet’ and I was interviewed for this by Maggie Aderin-Pocock, one of the show’s presenters. We spoke all about my beautiful tiny pieces of comet dust and you’ll be able to see some of these on the show. It’s also repeated a few times and it’s on iPlayer too. But first off, watch the news tomorrow because I might also be on there talking about comets to David Shukman who visited us at The Open University a few weeks ago in preparation for all of the exciting Rosetta-related news.

Other than that I’ve been trying to get the NanoSIMS up and running again after a bit of a problem. But I’ve only discovered more problems so my student is very patiently waiting to start his analyses. We’ll get there as quick as we can because he needs some data for a conference he goes to in September.

Catch a Comet at The Royal Society summer exhibition

Well it’s been a really fun week so far down in London for the annual Royal Society summer exhibition. I’m feeling slightly exhausted now but my fabulous team and I have spoken to so many people telling them all about the Rosetta space mission. People seem to be excited that we’re going to land on a comet in November, of course they are, it’s a very exciting event. I’ve also done a show and tell for the public this week where I got loads of great questions.

Well it’s been a really fun week so far down in London for the annual Royal Society summer exhibition. I’m feeling slightly exhausted now but my fabulous team and I have spoken to so many people telling them all about the Rosetta space mission. People seem to be excited that we’re going to land on a comet in November, of course they are, it’s a very exciting event. I’ve also done a show and tell for the public this week where I got loads of great questions.

I was lucky enough to attend two of the famous evening soirees which have been lots of fun with amazing food (even a ‘make your own’ apple crumble, yum!). We had the Duke of Kent around asking us about our exhibit and a lovely dog who took some great interest in one of our 3D printed comet models. All in all a fantastic week and we still have the weekend to go.

I was lucky enough to attend two of the famous evening soirees which have been lots of fun with amazing food (even a ‘make your own’ apple crumble, yum!). We had the Duke of Kent around asking us about our exhibit and a lovely dog who took some great interest in one of our 3D printed comet models. All in all a fantastic week and we still have the weekend to go.

I was interviewed by Quentin Cooper and so our Catch a Comet stand was featured on the Royal Society podcast which you can listen to here.

I was interviewed by Quentin Cooper and so our Catch a Comet stand was featured on the Royal Society podcast which you can listen to here.

I was interviewed for BBC News which will be featured later in the year but here’s a shot of the cameraman filming our beautiful lander model (we even removed the protective lid for him). Although, I have the say, the cameraman looks a bit stressed in this photo!

All set for ‘Catch A Comet’ at The Royal Society Summer Exhibition next week

So it’s been a very busy month so far with the end of this one and the start of the next getting even busier. I’ll be down in London all of next week at The Royal Society with the annual summer exhibition. I’ll be presenting the UK’s involvement in the Rosetta mission and our exhibit’s called ‘Catch A Comet’. We have a comet sculpture, Philae lander model, a plasma interactive game and lots of happy and enthusiastic scientists from the OU, Imperial, Kent and UCL who are ready to talk to you about the mission, and comets in general. We had a run through this week of the exhibit with our lovely scientist volunteers (close to 20 of them) and it went really well with everyone getting quite excited now.

Anyway, we kicked off today with a twitter Q&A which has been storified here so you can see what types of questions people had for us (and how we tried to answer them…including what does comet water taste like?).

If you can make it down to London next week (or if you’re there already) then pop by the Royal Society as there’s about 20 other exhibits in addition to us. It’s a whole building full of cool science and it’s on all week 🙂 See you there!